Arabic (

العربية al-ʻarabīyah or

عربي/عربى ʻarabī ) (

[al ʕarabijja] (help·info)

[al ʕarabijja] (help·info) or (

[ʕarabi] (help·info)

[ʕarabi] (help·info)) is a name applied to the descendants of the

Classical Arabic language of the 6th century AD. This includes both the literary language and the spoken Arabic varieties.

The literary language is called

Modern Standard Arabic or

Literary Arabic.

It is currently the only official form of Arabic, used in most written

documents as well as in formal spoken occasions, such as lectures and

news broadcasts. In 1912,

Moroccan Arabic was official in

Morocco for some time, before Morocco joined the

Arab League.

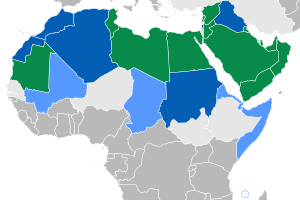

The

spoken Arabic varieties are spoken in a wide arc of territory stretching across the

Middle East and

North Africa.

Arabic languages are

Central Semitic languages, most closely related to

Hebrew,

Aramaic,

Ugaritic and

Phoenician.

The standardized written Arabic is distinct from and more conservative

than all of the spoken varieties, and the two exist in a state known as

diglossia, used side-by-side for different societal functions.

Some of the spoken varieties are

mutually unintelligible,

[3] and the varieties as a whole constitute a

sociolinguistic language.

This means that on purely linguistic grounds they would likely be

considered to constitute more than one language, but are commonly

grouped together as a single language for political and/or ethnic

reasons, (

look below). If considered multiple languages, it is unclear how many languages there would be, as the spoken varieties form a

dialect chain with no clear boundaries. If Arabic is considered a single language, it may be spoken by as many as 280 million

first language

speakers, making it one of the half dozen most populous languages in

the world. If considered separate languages, the most-spoken variety

would most likely be

Egyptian Arabic, with 95 million native speakers

[4]—still greater than any other Semitic language.

The modern written language (

Modern Standard Arabic) is derived from the language of the

Quran (known as

Classical Arabic

or Quranic Arabic). It is widely taught in schools, universities, and

used to varying degrees in workplaces, government and the media. The two

formal varieties are grouped together as

Literary Arabic, which is the official language of 26 states and the

liturgical language of

Islam.

Modern Standard Arabic largely follows the grammatical standards of

Quranic Arabic and uses much of the same vocabulary. However, it has

discarded some grammatical constructions and vocabulary that no longer

have any counterpoint in the spoken varieties, and adopted certain new

constructions and vocabulary from the spoken varieties. Much of the new

vocabulary is used to denote concepts that have arisen in the

post-Quranic era, especially in modern times.

Arabic is the only surviving member of the

Old North Arabian dialect group, attested in

Pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions dating back to the 4th century.

[5] Arabic is written with the Arabic alphabet, which is an

abjad script, and is written from

right-to-left. Although, the spoken varieties are often written in

ASCII Latin with no standardized forms.

Arabic has lent many words to other languages of the

Islamic world, like

Persian,

Turkish,

Bosnian,

Kazakh,

Bengali,

Urdu,

Hindi,

Malay and

Hausa. During the

Middle Ages,

Literary Arabic was a major vehicle of culture in Europe, especially in

science, mathematics and philosophy. As a result, many European

languages have also

borrowed many words from it. Arabic influence, both in vocabulary and grammar, is seen in

Romance languages, particularly

Spanish,

Portuguese,

Catalan and

Sicilian, owing to both the proximity of European and Arab civilizations and 700 years of Muslim (

Moorish) rule in some parts of the

Iberian Peninsula referred to as

Al-Andalus.

Arabic has also borrowed words from many languages, including

Hebrew,

Greek,

Persian and

Syriac in early centuries,

Turkish in medieval times and contemporary European languages in modern times, mostly from English and

French

General

Introduction

The rise of Arabic to the

status of a major world language is inextricably intertwined with the rise

of Islam as a major world religion. Before the appearance of Islam, Arabic

was a minor member of the southern branch of the Semitic language family,

used by a small number of largely nomadic tribes in the Arabian peninsula,

with an extremely poorly documented textual history. Within a hundred years

after the death (in 632 C.E.1)

of Muhammad , the prophet entrusted by God to deliver the Islamic message,

Arabic had become the official language of a world empire whose boundaries

stretched from the Oxus River in Central Asia to the Atlantic Ocean, and had

even moved northward into the Iberian Peninsula of Europe.

The unprecedented nature

of this transformation--at least among the languages found in the

Mediterranean Basin area--can be appreciated by comparisons with its

predecessors as major religious/political vernaculars in the region: Hebrew,

Greek and Latin. Hebrew, the language which preserved the major scriptural

texts of the Jewish religious tradition, had never secured major political

status as a language of empire, and, indeed, by the time Christianity was

established as a growing religious force in the second century C.E. had

virtually ceased to be spoken or actively used in its home territory, having

been replaced by its sister Semitic language, Aramaic, which was the

international language of the Persian empire. Greek, the language used to

preserve the most important canonical scriptural tracts of Christianity, the

New Testament writings, had been already long been established as the

pre-eminent language of culture and education in Mediterranean pagan society

when it was co-opted by Christian scribes. By this period (the second

century C.E.), Greek had ceased to be the language of the governmental

institutions. Greek, however, had resurfaced politically by the time of the

rise of Christianity as a state religion under the emperor Constantine (d.

337 C.E.,)--who laid the groundwork for the split of the Roman empire into

western and eastern (Byzantine) halves. By the time of Muhammad's birth

(approximately 570 C.E.) Greek had fully reestablished its position as the

governmetnal as well as religious vernacular of the Byzantines.

Latin had for a time

usurped the predominance of Greek as a governmental and administrative

language when the Romans unified the region under the aegis of their empire,

and it would remain a unifying cultural language for Western Europe long

after the Roman empire ceased to exist as a political entity in that region.

The main entry of Latin, on the other hand, into the religious sphere of

monotheism was relatively minor, as the medium for the influential

translation of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, the Vulgate, that was

the only official version of scripture for the western Christian church

until the rise of Protestantism in the sixteenth century.

Hebrew, then, was a

religious language par excellence. Greek and Latin, on the other hand, while

making invaluable contributions to the corpus of religious texts used in

both Judaism (the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint, was the

scriptual text of choice among the Hellenized Jews of the Roman empire) and

Christianity, were each languages that had extensive imperial histories

which preceded (and followed) the rise of Judeo-Christian monotheism to

prominence in the Mediterranean and had strong cultural links to the pagan

world and sensibility of Hellenism. It is only against this backdrop that

the truly radical break with the past represented by the rise of Arabic as

the scriptural medium for Islam coupled with its adoption by the Umayyad

caliphs as the sole language for governmental business in 697 C.E. can be

appreciated.

Background

and History

Arabic belongs to the

Semitic language family. The members of this family have a recorded history

going back thousands of years--one of the most extensive continuous archives

of documents belonging to any human language group. The Semitic languages

eventually took root and flourished in the Mediterranean Basin area,

especially in the Tigris-Euphrates river basin and in the coastal areas of

the Levant, but where the home area of "proto-Semitic" was located is still

the object of dispute among scholars. Once, the Arabian Peninsula was

thought to have been the "cradle" of proto-Semitic, but nowadays many

scholars advocate the view that it originated somewhere in East Africa,

probably in the area of Somalia/Ethiopia. Interestingly, both these areas

are now dominated linguistically by the two youngest members of the Semitic

language family: Arabic and Amharic, both of which emerged in the mid-fourth

century C.E.

The swift emergence and

spread of Arabic and Amharic illustrates what seems to be a particularly

notable characteristic of the Semitic language family: as new members of the

group emerge, they tend to assimilate their parent languages quite

completely. This would account for the fact that so many members of the

group have disappeared completely over the centuries or have become

fossilized languages often limited to mainly religious contexts, no longer

part of the speech of daily life. This assimilative power was certainly a

factor in the spread of Arabic, which completely displaced its predecessors

after only a few hundred years in the area where Arabic speakers had become

politically dominant . Thus all the South Arabian languages and Aramaic, in

all its varied dialectical forms, became to all intents and purposes "dead"

languages very soon after the emergence of Islam in the seventh century C.E.

2 Arabic even did

the same thing to the Hamitic3

language of Coptic, which was the direct descendent of Pharaonic Egyptian

and still an important literary and cultural language at the time of the

Islamic conquest. Today it survives only as the religious language of the

Coptic Christian community of Egypt, who otherwise use Arabic in all spheres

of their everyday lives.

In contrast, when Arabic

has contested ground with Indo-European languages or members of other

distant linguistic families, like Turkish (which is a member of the Altaic

family of languages that originated in central Mongolia), its record has not

been nearly so successful. For example, when Arabic was introduced into the

Iranian Plateau after the fall of the Sassanian Empire to the Arab armies in

the 630s C.E., it seemed to overwhelmingly dominate the Indo-European

Persianate languages of the region for a while. But by the late 900s, a

revitalized form of the Old Persian (Pahlavi) language had decisively

re-emerged as not only a spoken language, but also a vehicle for government

transactions and literary culture as well. This "new" Persian has remained

dominant in this geographical region throughout succeeding centuries and the

modern Persian spoken today in Iran is virtually identical with it.

Arabic was not the first

Semitic language to exhibit this tendency to completely overwhelm its

predecessors. Aramaic, the language of various peoples living in Syria and

upper Mesopotamia, had pioneered this pattern long before, having displaced

(though not suddenly and not necessarily at the same time) both the Akkadian

language of the people who had ruled the Tigris-Euphrates basin after the

Sumerians (who spoke a non-Semitic language), and Hebrew and other Canaanite

tongues that had been used along the coastal strip of the Levant.4

By the time Jesus was born, for example, the Jews used either the Jewish

dialectical version of Aramaic or Greek for most of their writings and in

daily life. Similarly, the Aramaic dialect of the city of Edessa, known as

Syriac, became the language used by the Christian communities east of

Constantinople.

Even as the Aramaic

dialects grew to dominate the Levantine areas and became the lingua

franca of the Persian empire, in the south--less subject to the unifying

pressures of complex imperial systems of government and education--a much

more fluid and less textualized language situation prevailed. Old

civilizations had arisen on the southern fringe of the Arabian peninsula,

built on the profits of trade and commerce in the area, particularly the

long-distance incense trade. The succession of sedentary dynasties that

controlled this land of "Sheba" (or, more properly, Saba) used different

forms of a language usually called now "Old South Arabian" of which the

dominant dialect was probably Sabaic. Our main records of these languages

comes from inscriptions rather than written documents, so our knowledge of

how they first developed and later changed is necessarily sketchy. Farther

to the north, a tribal, nomadic lifestyle dominated, and although we have

fragmentary epigraphic records of some of the dialects these tribes used,

our current knowlege about the actual linguistic situation prevailing in the

area is even more incomplete than our knowledge of the South Arabian

kingdoms. 5

Although echoes of the

glorious past and great achievements of the Sabeans and other peoples of the

south would continue to resonate in the literature of the Arab Muslim world

throughout its long history, scholars of Arabic literary history have always

focused their attention on the nomadic northern Arabs in their accounts of

how this literature arose. The overriding reason for this is a linguistic

one: the tongue used throughout the Arab world today, and known as fusha

or "Standard Arabic," is the same language used by these northern Arabs,

crystallized in its written form in the revelations of the Qur’an as

recorded in the early 600s C.E..

Though the major southern

language, Sabaic, and Arabic are closely related to one another, they are

definitely separate languages, as different as modern-day English and

German, and probably just as often mutually unintelligible as not. Sabaic is

almost certainly the older of the two languages, being used for inscriptions

as early as 600 B.C.E., while the first evidence we have of Arabic as a

written language occurs 900 years later, in an inscription dating to 328

C.E. When the two languages mixed and met after the rise of Islam, however,

Northern (Mudari) Arabic--backed by the religious authority of the

Qur’an--supplanted its older cousin completely as a language of high

culture. Sabaic survives today only in isolated pockets of territory where

various dialectical versions continue on a purely spoken level. Written

communication in the south is all in Mudari Arabic. The relationship between

Mudari and Sabean--as well as the relationships among the other Semitic

languages can be seen in the following chart :

Although Mudari Arabic belongs to the South Semitic

branch of the Semitic language family (see chart), it seems to have shared

an unusually close relationship with a Western Semitic language as well:

Aramaic. This is largely due to the fact that the Nabateans--a northern

nomadic tribe that moved onto the fringes of the oikoumene in the

300s B.C.E. and settled down to control the northern terminus of the incense

route--seems to have spoken a language very close to Arabic, but they

used Aramaic as their official language of written communication.6

The reason why it is so

important to stress a close relationship between Arabic and Aramaic is that

the first documented example we have of Mudari Arabic--an epitaph from a

tomb about 100 kilometers southwest of Damascus--is written in the

(Nabataean) Aramaic alphabet, although the vocabulary and syntax is

virtually identical with the "classical" form of Arabic codified in the

Qur’an. This inscription, known as the "Namara inscription" for the place

where it was found, is important historically as well as linguistically. It

was discovered in April of 1901 by two French archaeologists, R. Dussaud and

F. Macler, in a rugged portion of southern Syria (about 60 miles southeast

of Damascus and almost due east of the Sea of Galilee). Namara was once the

site of a Roman fort, but while the archaeologists were exploring the area,

they came across a completely ruined mausoleum that was much older. This was

the tomb site of Imru’ al-Qays,7

the second king of the Lakhmid dynasty, an important family in northern

Arabia that at that time had been allied with the Byzantines and would later

move to the east (to the area around modern-day Basra) and become clients of

the Sassanian Persians.

The Namara inscription was

carved on a large block of basalt which had originally served as the lintel

for the entrance to the tomb. It identifies the occupant of the tomb as

Imru’ al-Qays, son of ‘Amr (the first Lakhmid king), calls him "king of the

Arabs," and gives some information about his notable exploits during his

reign. Then it gives what is perhaps the most important single piece of

information on the inscription: the date of the king’s death, 7 Kaslul

(December) of the year 223 in the Nabataean era of Bostra (=328 C.E.).

Presumably the tomb was constructed not long after Imru’ al-Qays’s death, so

this means we have a firm time frame in which to place the inscription.

In 1902 Dussaud published

a drawing of the original inscription in the Nabataean alphabet, a

transliteration of the characters into Arabic, and a tentative translation

of the result into French. His Arabic transliteration and the French

translation are given below:

Ceci est le tombeau

d’Amroulqais, fils de ‘Amr, roi de tous les Arabes, celui qui ceignit

le diadème (al-tadj), qui soumit les (Banou) ’Asad et (la tribu) Nizar

et leurs rois, qui mit en déroute Ma[dh]hij, jusque’à ce jour, qui

alla frapper Nedjrân, ville de Shamir, qui soumit la tribu de Ma‘add,

qui répartit entre ses fils les tribus et les départagea entre les

Perses et les Romains. Aucun roi n’a atteint sa gloire jusqu’à ce

jour. Il est mort l’an 223 le septième jour de kesloul. Que le bonheur

soit sur sa posterité!8

What was most striking

about this inscription for Dussaud and his fellow epigraphers was not only

that it pushed back the history of Mudari Arabic back almost 200 years

earlier than the previous oldest inscription, which had been dated to 512

C.E.,9 but that the

language was so close to the Arabic of the Qur’an. Apart from a few words,

like "bar" for "ibn" (son), which are clearly Aramaic, and some dialectical

forms, like "ti" for "dhi" (this) and "dh‚" for "alladhi" (which), the

vocabulary and syntax does not differ noticeably from the "classical" Arabic

of the sixth century C.E.

For over 80 years, this

was taken as the definitive rendering of the inscription, but in 1985 James

Bellamy of the University of Michigan published an article based on his

minute re-examination of the original stone, now located at the Musée de

Louvre in Paris. Professor Bellamy’s conclusions about the inscription being

in Mudari Arabic confirm Dussaud’s, but he has revised some of the latter’s

reading of individual words and phrases, to come up with a new rendering

that seems to have won fairly wide acceptance,10

The new version in Arabic transliteration, accompanied by Bellamy’s English

translation are given below:

This is the funerary

monument of Imru’u al-Qays, son of ‘Amr, king of the Arabs; and[?] his

title of honor was Master of Asad and Madhhij. And he subdued the

Asad¬s, and they were overwhelmed together with their kings, and he

put to flight Ma(dh)hij thereafter, and came Driving them into the

gates of Najran, the city of Shammar, and he subdued Ma‘add, and he

dealt gently with the nobles Of the tribes, and appointed them

viceroys, and they became phylarchs for the Romans. And no king has

equalled hisachievements. Thereafter he died in the year 223 on the

7th day of Kaslul. Oh the good fortune of those who were his friends!The dating on this

inscription allows us to conjecture that by this time (328 C.E.) Mudari

Arabic had become an independent language with many of the features we

associate with modern Arabic but manifestations of its use over the next

three centuries remain frustratingly fragmentary. Only in the mid-seventh

century do we begin to have more than isolated bits and pieces of epigraphic

evidence for its existence, and by this time the language had become the

preferred medium of communication for a growing empire, as well as a dynamic

and appealing new religion.

.jpg)